Taking part in the discussion:

Stepan Subbotin is an artist, a member of the ZIP group, and a co-founder of several art initiatives — Typography Center for Contemporary Art, the Pyatikhatka residence (Anapa, Krasnodar region), and the educational platform KICA (Krasnodar Institute of Contemporary Art). His artistic practices are based on working with communities, creating installations and places for co-creation, education and radical fantasy. Recently, as part of the ZIP group, he is engaged in anarcho-local research of the utopian community “techno-peasants”.

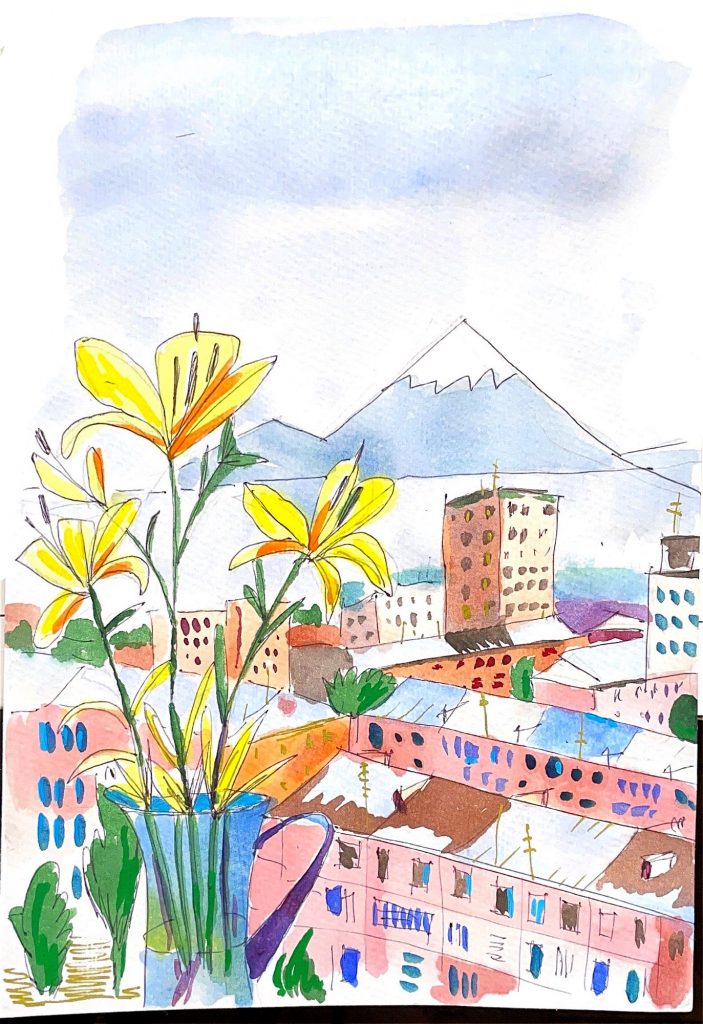

Marianna Kruchinski is a curator at Typography Center for Contemporary Art since 2017, an independent cultural worker. Her interest lies in labour and leisure theories and practices, solidarity methodologies of self-organisations, archival practices and tracing their imperial roots. In 2022 she organised an emergency residence program in Yerevan, Armenia for cultural workers from russia.

Elena Ishchenko is a curator, researcher, co-organizer of the League of Gentlemen. She joined the Typography CCA’s team in 2017 and was involved in exhibition and art projects, as well as organising repairs and managing the budget. Her practice focuses on self-organised initiatives and a decolonial approach. He runs the Empires will die Telegram channel, in which he talks about Russian imperialism.

Disclaimer: This is a long text dedicated to Typography, the Krasnodar Center for Contemporary Art, and a discussion of our strategies and tactics in the past and present. This conversation is important to us as an opportunity for public reflection and dialogue with other institutions. If you don’t want to read a big text devoted to the internal processes of one institution, please go directly to other conversations in the Translocal Dialogues project.

In August 2022, Typography turned ten years old. We were going to celebrate this date with a festival, discuss what institutions dealing with contemporary art are needed for today, and talk about our future work strategy.

We worked on this program until February 24, 2022, when russia launched a full-scale military invasion of Ukraine. We released several anti-war statements on social media and froze our public program in order to repurpose it. But because of the new laws introduced by the Duma literally every day, it soon became apparent that open anti-war activity in russia is now impossible.

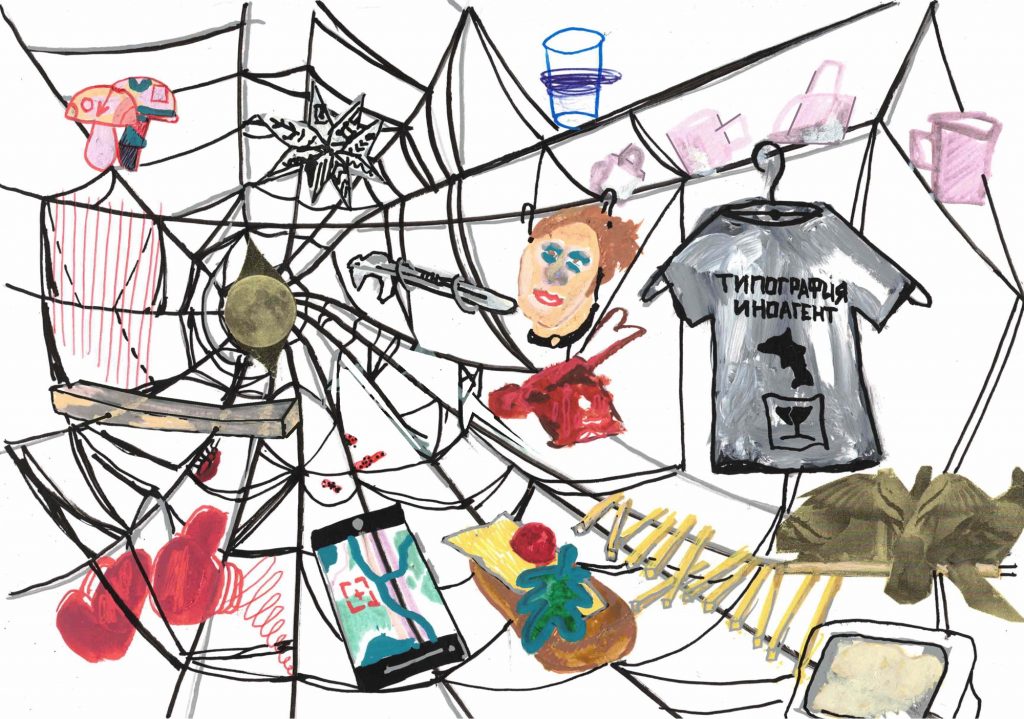

On May 6, 2022, the Ministry of Justice of the russian federation declared Typography a foreign agent. This status does not mean direct persecution but significantly complicates the work, creating additional obstacles and threats. We closed the space in Krasnodar to avoid endangering its workers and visitors, expecting further prosecution. Among other things, we’ve already received calls from the police about our anti-war statements.

Most of the Typography team left Russia. At the moment — January 2023 — some of us are in Yerevan (Armenia), Cologne and Berlin (Germany) and the cities of russia.

We are trying to continue our work, look for suitable formats, join and create the necessary structures of resistance, support and information sharing. Previously, following the logic of decentralisation, we tried to focus on the locality of Krasnodar and the Krasnodar Krai. Now our institution follows the logic of translocality — participants disperse in different countries and contexts, slipping away for the safety of those who remain in russia.

The KICA — Krasnodar Institute of Contemporary Art — is still running, now online. The new residency in Yerevan is open for artists and cultural workers from russia who cannot leave but need to rest, maintain and acquire cultural ties. Community radio “Fantasia”, created by a team of Typography workers and their friends, continues its work.

Typography has crossed its ten-year milestone at an entirely different point than we expected. We decided to make a public project dedicated to this event/period nevertheless, but to devote it to things that are on our minds today — war, exile, loss of home, (in)ability to mourn and celebrate. To do this, we chose the format of dialogues and invited artists and researchers from Armenia, Artsakh, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Iran, Ukraine, Yakutia and russia, who live in different cities and countries, to the conversation.

For the first dialogue, part of our team came together to discuss Typography itself, our tactics and strategies in the past and present. This material is divided into four parts devoted to different topics — the collective, institutional economics, locality, and political subjectivity.

Collective and Collectivity

Elena: Our first topic is collectivity and personal responsibility. What is the Typography team? How did this community develop? Stepa, can you tell us how it was in the beginning? How did you perceive the collectivity of Typography? Did you think about it back then? How were your roles distributed?

Stepan: At first, everything was divided into KICA and Typography. KICA 1 was an exhibition platform we, the ZIP group, managed. Typography was a coworking space and a hostel, and Kolya Moroz was in charge of them; he also interacted with administrators. Our team was us and Kolya, a team of enthusiasts.

Marianna: What years are these?

Stepan: 2012 — 2013.

Marianna: So back then, you didn’t do any maintenance at all?

Stepan: On the contrary, we did lots of maintenance: cleaned, moved stuff around, refurbished the space, assembled furniture and painted walls. Kolya did this as well, perhaps even more than us. In recent years, Typography has become such a unified labour entity where everyone was included in all processes. And at the beginning, it was different: there were administrators who, for example, simply monitored coworking and were not actively involved in organizational activities. We didn’t understand what coworking was at all. We did something in the workshop, worked with artists, posted on Facebook and VK, mounted exhibitions, wrote texts for them. And Kolya fully managed the financial and bureaucratic parts.

Marianna: And who was in charge of the social networks?

Stepan: Eldar and I, Vasya and Zhenya2 too, and Sasha Rodionov initially participated a bit.

Elena: And how did you start taking part in managing everything that happens at the Typography?

Stepan: When Evgeny Pavlovich3 joined us. There were people whom he tried to make the managers of the Typography, but it didn’t work out very well. Evgeny Pavlovich paid for utilities and rent — the main lines of expenses. The hostel brought in some money, which was used to support it.

Elena: Have you tried to discuss what Typography is and how it should develop with these managers? I had a feeling that the managers just wanted to “tidy up” and were generally indifferent to what you were doing.

Stepan: Our main goal was to develop art and the environment, create a platform for exhibitions, help artists create their personal projects and invite curators to do group projects. We wanted our events — exhibitions, films, lectures — to be free of charge; it was essential for developing the artistic environment.

But there was another direction — an attempt to make some kind of profitable business, be it coworking, a hostel or renting out space. Or even a children’s creativity school, which both managers and we liked a lot. But in general, these two directions did not intersect.

Elena: But at the same time, you never thought about getting paid for what you do.

Stepan: We understood this was a considerable expense for those investing in Typography. And it was unrealistic to earn money for our own salary because the exhibition hall and workshops were much larger than the coworking space that we rented out. Plus, we have always had very low rental prices. And back then, space looked quite freaky: maybe, people wanted to do something there, but they were put off. Therefore, it was unrealistic to earn a salary for ourselves. Once Sasha Rodionov brought “Philip Morris” for some event, and it did us almost a month of rent. He also made the Typography website, helped maintain it and set up targeted advertising.

Elena: And why did the space look like that?

Stepan: We had everything DIY, but it was cool — a very lively thing. But “Kublog”4 was writing about how Typography is a pigsty.

Elena: My question is more about the feeling of collectivity. When I started doing something at Typography in 2017, there was a sense of crisis. As if you were tired but still tried to do something with the last of your strength, although you had a lot of your own projects. Evgeny Pavlovich was furious because of the dirt, hiring the manager, Olesya, who changed the curtains but had little understanding of what this place is about. There are also Sonya and Tanya, administrators who were also not very deeply involved in the process.

Marianna: Lena, what does participation even mean in this stage of the Typography’s history? Is it only the creation of events, or is taking out the trash in time or changing cat Pixel’s litterbox also participation?

Elena: I mean that at the time, I didn’t have a sense of collectivity, as if everyone was doing something of their own and didn’t really discuss the future or what the hell all of this is about.

But the issue of participation is critical. Now I would say that, yes, I think that everything is participation. At the time, to be honest, I didn’t think so. Did you, for example, consider Sonya and Tanya as part of the Typography?

Marianna: Do I understand correctly — I don’t want this to sound harsh — but was it a service activity supporting artists’ activities?

Stepan: Some events, like the New Year’s Market, involved everyone. Other than that, everyone was minding their own business. It seems to me that until 2018, we generally considered artists doing something in the space as Typography participants. In the first catalogues (First and Second), there is a spread listing them — about fifteen people. And the direction associated with the commercial side was like some other organism.

Stepan: Well, service… We never had the money for exhibitions, none of the artists received a salary or fees. I wanted the administrators to be included in developing the artistic environment, but I often faced a sort of dissonance. I did not feel offended by those who received a salary because they were doing work I would not like to do.

Marianna: Cool. Now that we have discussed this, I have a better understanding of how the collectivity of Typography developed. I also understand now why some artists were communicating with me the way they were. Their participation in Typography was considered work, and they saw it as a place they were forming. Therefore, some jealousy arose when Lena and I came: we understood collectivity differently, as well as the public program. We tried to remove the separation between the production and demonstration of art and the so-called rental events or events that help to pay bills. It seems to me that 2017 was a transitional phase, when people who went to the Typography every day and hung out became guests, so to speak, and not the collective that formed the Center.

Stepan: The venue has changed, and the scene has also changed. When we were creating KICA and then Typography, there were no places in Krasnodar where one could come with an idea for an exhibition. The ZIP group tried to work with exhibition halls and other venues, but there was too much bureaucracy. Typography was a friendly place: you come — and immediately get on with the work. You get help with installing everything, with writing texts. Lots of people had their personal exhibitions in Typography. It was a platform for experiments, a laboratory. There was no budget, but there was a lot of energy and enthusiasm, even with older artists like Valery Kazas. And Julia Kazas even became an artist in Typography. As well as some “monster” artists, such as Valera-the-Witness.

Elena: Generally, I perceived Typography in a different way, more as a place in the city, in the country, which is visible, working not only for the artists participating in the process but also outside, for those who just come there. And this seemed to require a different sort of collectivity, where there are some roles and areas of responsibility, and everyone working is aware of this responsibility.

Marianna: But is such interaction possible without the stage that Stepan is talking about? Is it possible immediately, without any material resources, to build such a system within which everyone is responsible for something and is endowed with material and symbolic capital? Is it possible to do this when you are 20 years old?

Stepan: The approach I’m talking about is also based on the fact that we perceived ourselves as lonely artists in Krasnodar. To jump up these processes, you need an art scene. The ZIP group is already a micro-artistic environment. But there was a need for a larger community that could stand up for Typography against all these painting exhibitions in the “Lestnitsa” or “Yug” galleries. We were creating a platform together with artists so that we are not branded as a pigsty, to not be led by some “higher taste” which considers painting to be the only form of art.

Marianna: I remembered meeting with Swedish artist Sam Hultin. Describing the activist practice of Eva-Lisa Bengtson, who opened the first trans club in Sweden, he always asked the question: what makes vulnerable groups of people open their doors and unite? This same question comes to mind when I think about the collaborations we have initiated with urban communities: why did we open our doors to them? Was it an association to protect against an aggressive environment, or were we genuinely interested in each other?

For me, with the relocation of the Typography to 5lit.Y Zipovskaya Street, a vital period began in the Center’s collectivity. The realization came that it was impossible to get hired by Typography through an advertisement: if you don’t understand what the Center is about if you didn’t go to events, exhibitions, or at least to markets, didn’t study at KICA, then you cannot become part of this collective. We hung out all the time. Misha, Sonya and me, and then Nikita and Max, who joined Typography in 2021 — we probably spent the maximum number of night hours in the new space — jamming together, doing movie screenings and eating chips. It is worth noting the role of Stepan P. and “Buffet” in this joint pastime.

On the other hand, it is important to note that the Typography community was very reserved from the very beginning to the last days of its work in Krasnodar. Exhibition opportunities were not unlimited. When I, super nervous, suggested my exhibition idea in 2016, Eldar quite harshly refused me because I was not an artist. Moreover, the rules of inclusion or exclusion were quite intuitive and those who joined the team at different stages interpreted them differently. There was no manifesto or code you could refer to, and in 2022 I had a lot of tricky situations because of this.

Elena: After our team was forced to disperse, I realised that I don’t really like working in a team. It is often easier for me to do everything myself than to interact — because of some kind of perfectionism and standards. Now I understand very clearly that many have suffered from this. For example, the ZIP group, especially when building an exhibition. Nevertheless, thanks to the work in Typography, this perfectionism has decreased.

If we come back to collectivity. When talking about Typography earlier, I usually introduced the team in the form of a diagram. I said that each person on a team adds a new direction — unlike ordinary institutions, where these directions are fixed. But this is only partly true. Yes, when I arrived, I began to structure everything, including the exhibition program, so that it would meet the goals and objectives of Typography. This direction appeared, as well as budget sheets (I was shocked when I learned that you didn’t have them before!). When Marianna came, she brought in the public program and cinema. But when I say that Lera came and started working on the archive, this logic breaks because it’s not true: Lera came to work as an admin and to sit behind the desk. Nikita and Dasha didn’t bring in new directions either, but that doesn’t make their participation less important.

You tried to bring this collectivity together and motivate people to take the initiative: Misha and Fantasia community radio, Nikita and design, Lera and recycling separation, Dasha and art mediation. But Typography for them was already a cool place where something dope was happening; they wanted to be involved and do something there, but taking responsibility and starting something new was more difficult.

Marianna: Probably, this was the case for the first Typography space as well. As Stepan says, it was the only space like that. Such a place in the city center and at the same time is control-free.

Elena: Marianna and I were discussing how there was a huge room, 40 square meters, supposedly a workshop, but in fact, everyone just smoked there.

Stepan: There weren’t enough places like this in the city. We made it because we needed it ourselves; that’s why people came there. Many wanted to invest because they saw it as an opportunity for themselves. As an artist, I wanted to develop the scene, to do projects — and do this at home, not somewhere already “cool”, like New York. Someone came, and they dreamed of sitting at a beautiful table, and Misha wanted to make a musical program, something else — unusual exhibitions. Here everything depended on the vision you had.

Elena: Yes, it’s interesting: you spoke about collectivity as a circle of artists who do projects. And we offered those who wanted to become part of the Typography not to do exhibitions but some kind of managerial work — to organise these opportunities for others. Although the majority still wanted a solo exhibition.

Marianna: Let’s wrap this topic up with the last two questions: how do we understand collectivity now and, maybe, make a micro-forecast for the future.

Elena: The most valuable experience from the Typography collective for me was during those days in February – March and then a joint move to Yerevan. How we used to get together daily at Typography, draw stickers and constantly discuss what to do. It was a moment of such strong unity when I understood why Typography exists and why we are all here together. I’m talking about it now — and I get goosebumps. And then how we constantly gathered in an apartment in Yerevan.

Then we ended up in different cities, but I still feel the value of this connection. Now I see it manifesting itself through KICA: how every time we rethink the program and try to comprehend what is happening in the world and with us through it. And I am glad that we managed to talk with Eldar and exclude him from the KISI team — I really want to see that we share the same views with the people I work with. The project “Translocal Dialogues” — is such a strange thing, but it’s also an attempt to get closer to understanding what is happening.

Stepan: Nowadays, I start every morning with messages. Collectivity and the desire to support it — is the most important thing. Previously, there was the context of Krasnodar, within which we did all this. It held everything together, but now it is gone. What is left is only our connections, which continue to develop in some new places. In Yerevan, for example. I often think about what is happening there, much more often than about Krasnodar, where there is nothing left for me now except for the house and the people who continue to live there. With them, I try to keep in touch through calls and texts. The place no longer bears significance. If we preserve our collectivity, we can share the experiences we are now living through. I even believe in online meetings now. At the beginning of the war, it was difficult with KISI, but then it became a necessity and a source of support.

Marianna: I don’t want to repeat what you said about the importance of this year, but I would like to share my joy from the fact that the employees of the Typography stay in touch and try to support each other outside of salary incentives or the space that we discussed as a unifying factor. In this collectivity, someone lights up, and someone flickers quietly. But she survived. And this is surprising because there were no guarantees. Now I especially believe in this collectivity and connection, which already shows itself outside the Typography as a space and even self-organization.

Good economy

Stepan: A good economy is like a good russian.

Marianna: It seems that we will appear here as bad russians.

Stepan: Possibly.

Elena: We have always talked about Typography as non-governmental, independent. What is behind these words? What ensured this independence? From whom did we take money, why, and what did it cost us? Let’s discuss where the understanding of some kind of general budget, expenses and incomes, came from. From our conversation, I understand that you did not think about it for a long time and emphasised the separation between commercial activities and art practices. This was a common misconception, widespread at a certain period. I remember, for example, when we tried to monetize aroundart.org, there was also an opinion that you don’t give or get money for a good deed. Did you also feel that way in the beginning? Why?

Stepan: Because at that time, it could not be mixed.

Elena: Why?

Stepan: Krasnodar is a place of hellish capitalism and exploitation, where it is impossible to evaluate social activity in monetary terms. For example, exhibitions: we didn’t charge for entrance for a long time, and people used Typography as a free toilet, just passing through the exhibition hall. When we started selling tickets, people began to look at the art. It’s like when you pay, it means it’s worth something. But who will give money for exhibitions — I don’t mean visitors, but rather companies? Therefore, it was essential for us to distinguish: we will not make some bullshit for tobacco advertising and call it art.

Marianna: Did you try to define what Typography sees as art?

Stepan: Well, a stick, a rope, a concept — who will pay for this? How can this be translated into commercial terms? It was incomprehensible.

Elena: This is also about developing the artistic community and one’s place within it. It’s like when you start getting money for something, you find yourself outside the community: we’re all doing something together here, but someone gets the money. You seemed to perceive it as a collective practice but not as a job at all.

Stepan: If we have perceived it as a job, we wouldn’t do it.

Marianna: Why?

Stepan: You get paid for doing a job. If you work for free, this is self-exploitation that you will want to escape from. We perceived it as a social activity, which at that time had no value. We had to prove to Krasnodar, filled with commercial garbage, that there’s more than fashion shows and glossy crap, where artists were usually employed. The division into commercial and non-commercial was a way of dealing with glamour and gloss.

Elena: It seems to me that this is false logic. Money must be paid not only for what is sold but also for what brings some kind of social benefit.

Stepan: Yes, and we wanted to prove that this is a benefit without mixing it with commerce.

Another question is where to get the money from. Sometimes we did something on a barter basis for glossy magazines or tool shops in exchange for mounting materials, a screwdriver or a jigsaw. But we didn’t call it art and tried to distance ourselves from it.

Elena: I remember when I was telling Krasnodar journalists or potential partners that Typography is a non-commercial space, they did not understand at all what it was about, how something could exist if its goal was not profit. Where did Typography get the money from in the beginning?

Stepan: First — from Kolya, then — from Evgeny Pavlovich, and that’s it.

Elena: When did you get the idea of patronage?

Stepan: At first, it was a system that wasn’t designed to work long-term; we came up with some Patron club cards together with Sasha Rodionov. People donated 100, 500 rubles each, and someone brought 3000 rubles — we called everyone partons. I remember how we collected a hundred thousand rubles and paid off part of the rent debt. We learned about this patronage system from Anton Belov [Director of the Garage Museum], who, at that moment, in 2013, was implementing it at Garage. This call for patronage, in fact, was a media event — and Evgeny Pavlovich reacted to it and noticed us. In fact, he became not a patron, but a philanthropist, because he entirely financed everything.

And the real patronage system began to take shape in 2017 when Typography was already well-known when there was a program: exhibitions, cinema and a children’s school. The next patron was Valery5. And then the rest.

Elena: As far as I remember, patrons’ contributions covered only the rent of the space, and in the new space, they were usually not even enough for that. At the same time, rent was half the budget and a little less than half in the last couple of years. These contributions were very important in ensuring we would still have that space next month. At the same time, for me, communication with patrons required great emotional strength; I felt a certain hierarchy. Of course, thanks to them and together with them, we did a lot of useful things, but it seemed that we had different views even on Typography’s purpose.

Stepan: I am super grateful to all the patrons and consider many of them to be part of our team. We weren’t close with each one, but there were many of them: not one or two, but a whole collective of people. And this is one of the important things that Typography managed to achieve.

Marianna: It’s cool that you think so. It’s great luck that you communicated with them without feeling this hierarchy. Perhaps they continued to support Typography precisely because of that. For me, the most problematic was the need to appear as an expert from the world of the mysterious and sublime culture, and I didn’t want to participate in this masquerade. Therefore, it was vital for me to build a broad network of support in the city so that there are many people who contribute one ruble instead of one person who, say, gives three hundred rubles. Patreon seemed like a potentially more sustainable system.

Stepan: Patronage is also about work and transformation. At first, the patron supports you because it is fashionable, and then they begin to understand what you do. By the way, patrons are also successful people and influencers. In a normal society, we could continue working together to make a change.

Marianna: Do you really believe that?

Elena: For me, this is also an ideological issue. I adhere to leftist views when it comes to the structure of society and the economy; patronage contradicts them. The goal of our work is for capitalism to cease to exist; at the same time, we take money from those who earn it within this very system. Like in this meme, all cultural institutions are far-left in press releases, but in how they operate — they are far-right. Of course, that wasn’t quite our case. We didn’t have oligarch patrons, and, I guess, we didn’t have people building some kind of dishonest or corrupt business…

Although it’s hard to talk about it, what does an honest business mean in russia? In any case, even honest business involves procedures that produce inequalities and hierarchies. How, for example, to explain to the patron that everyone in Typography had equal salaries or that we want to build a horizontal team where there is no “boss”?

Marianna: How to explain that what we do can threaten the business of a person who supports us? How do we, in principle, explain to him what we actually do? I think, in our case, patronage is a deeply problematic practice.

Stepan: Everything is problematic in russia. Damn, I’m sorry I interrupted you.

Marianna: If it weren’t for russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, we would have survived for a couple more years, and I think we would have had a colossal crisis related to this support system.

Stepan: But patronage is something that requires elaboration and time. I also associate the patronage support system with total distrust of the state. We trusted private institutions instead, even if it was Garage or V-A-C, created and sponsored by oligarchs.

I think Evgeny Pavlovich believes in art as a socio-political tool, although we should ask him about it. There were several times when he was ready to withdraw his support but stayed with us in the end. I remember when he first became a patron, he came to the Typography for the opening of the of EliKuka group exhibition, where there was basically porn screened all over the space; everything was in smoke because they fried sausages on lamps and cooled them with fire extinguishers. “What the hell? Where am I?”

I think that other patrons also understand art not only as beauty but as an activity that changes society and the city.

Elena: Yes, Evgeny Pavlovich even buys artworks to support artists. But for many, the “Most” auction was something that shows that the art scene is progressing: the more works are sold for more money, the more developed the art sphere is6. This is a market model that they understand. What do I see as a sign of development? When artists stop just painting and begin to think of art as involvement in social and political processes, that it’s not making pretty things, it’s an ideology. If you make art without ideology, then you’re kind of…

Marianna: … fooling yourself.

Elena: Yes. And it seems to me that Typography has demonstrated this since its foundation, even though some patrons seemed to still have come for pretty things.

Stepan: Well, it was a mutual exploitation. We turned a blind eye to the “Most” auction because [its founder and patron Roman] Levitsky helped us with design and gave the auction’s proceeds — a million rubles — to Typography.

I think that people who sincerely support Typography can be considered like-minded people. It was never fashionable; people got nothing out of it. You can become the patron of the trendy Garage, or you can become the patron of the Typography. You sit at dinner in a restaurant and say: “I am the Typography patron, “and they ask you: “What is this?”

Marianna: You can apply different scales. Garage is cooler on one scale because you sit at the same table with [Roman] Abramovich. And on the other scale, you can spend thirty thousand rubles a month as a Typography patron, but you have the same status.

Elena: I don’t think that in russia the institution of patronage worked as an institution of symbolic capital at all: neither in Garage nor in our case. Alisher Usmanov is the patron of Garage, so what? If he tells his friends about it — they won’t give a fuck.

Okay, now let’s talk about salaries. The ZIP group received symbolic capital. Then, in 2017, Typography received a development grant from Garage, came Oleg, the only director of the Center, and then I joined to be in charge of exhibitions. And Oleg decided how much he would receive (I think it was fifty thousand rubles), and I asked for twenty-five thousand rubles.7

Marianna: It seems to me that the understanding of work in the cultural sphere as something that should be paid is not so old.

Stepan: We did a project at a big exhibition in Berlin in 2015, and no one also paid us a fee. Even per diems were something, we had to fight for. The general attitude was like: you get to show your work in Berlin, so you can put this in your CV — that should be enough.

Elena: It seems to me that this conversation is quite old. In 2011, there was a discussion held as part of the 10th anniversary of the May Day Art Workers’ Congress, co-organized by the “Chto Delat?” group. Zhenya Abramova researched this issue and wrote a legendary text on the labour of “girls”. But it’s as if this conversation begins anew for each new generation. Speaking about salaries, I remembered Levitsky claiming that if I had a salary of two hundred thousand rubles, I would be able to only work for Typography. And I tried to explain to him how it works: that we are not investing our resources in a capitalist company built on competition, that knowledge and skills, on the one hand, are important to obtain in different places; on the other hand, they need to be shared.

While we’re on the topic of “good economy”, it is also necessary to say that independence in the case of Typography meant constantly being on the verge of survival. When we talk about patronage, it’s not millions of rubles, expensive projects and big salaries. It’s survival. And if we more or less knew that we had money to pay for rent and utilities next month (three hundred and thirty thousand rubles a month), this was not always the case with salaries, plus we had to find additional funding for each project. Looking for money and then writing financial reports made up a significant percentage of our work time, and I’m grateful to our patrons for trusting us, never asking for reports, never even thinking about controlling our program.

By the way, we haven’t yet discussed rental events, many of which pissed us off. We had to endure hookahs or some posh overdressed birthday parties in the Typography to get money for something else.

Marianna: Yes, it turns out that this practice has been around since 2012, no matter what we thought. And it is essential to mention the victims of these rental events — those who were on duty until 3-5 o’clock in the morning.

But I would have never traded all these obstacles for being state funded in russia.

Stepan: Yes, for example, the Houses of Culture had to hold events of [pro-Kremlin political party] “united russia”. In this sense, patrons’ support reflected an understanding of state violence and was a kind of attempt to overcome it together with the artists.

Marianna: To be honest, I don’t think so. Rather, the patrons believed in you.

Elena: Now, the material side of the Typography is moving into the grant-based stage. After the beginning of a full-scale war, we decided to give up the space (I believe we decided this not long before we were declared foreign agents), and I was frankly relieved: we no longer needed to raise money every month, even though it was for the space that everyone loved, that gathered people. But in a situation of war, it was simply impossible to maintain this space and its purpose.

Stepan: Although it was so cool and important.

Locality

Marianna: Now, let’s talk about locality and resisting centralization. And let’s touch on the topic of space since we brought it up.

Stepan: I feel sorry for the new Typography space; it didn’t have time to fulfil its potential. And I got really tired of the first one. I knew every hole in the wall there. I walked on the metal floor and felt like it would stay with me for life. I got so fed up with this.

Elena: When the rent in the first space doubled in price, I was contemplating if we needed space at all. I talked to Stepan, and he had no doubts that space was needed. My question was, why should we pay a tremendous amount of money to some landlord when we can spend this money on projects and fees and do something cool in different places?

Stepan then said that the patrons would not support us if we did not have space. And then we discussed this with Marianna — you said that space is crucial for the city’s environment because people perceive what we do in general, not through separate projects. Many didn’t necessarily go to the Typography, but they could be proud that their city has such a center — modern, cool, new and young. These epithets describe something that was more or less associated with the place, not the projects.

Marianna: Yes, I remember the historical moment when I realised the importance of Typography as a space — when a pink lamp was hung in the old Typography in a wall niche near the entrance. This lamp was in front of the administrator’s desk, where entry tickets were sold, so people just came in to take a picture and leave. Instagram had a million of these photos in pink light. In the new Typography, especially with the “Buffet” and a DIY tennis table, they also came to spend time in a clean, pretty space without strict rules or judgemental stares.

Elena: When preparing for the conversation, I thought about what we meant by the development of the local environment and decentralization — and how people who wrote texts about us, interviewed us and conducted research understand this? What do we mean by decentralization? I remember how Fyodor Smolyakov wrote that you can’t call the creation of a new center decentralization, even if it is the Typography center. For me, decentralization has always been about redistributing resources — money and attention. And Typography, of course, made a considerable contribution to decentralization.

But if we are talking about the development of the local environment, then what was it? We say that people came to take pictures and drink coffee — they came to be in the space. But did it reflect the values we expressed through our projects in the first place? Or did we, after all, fall into the same liberal logic that you can see in the sidewalk improvements by Strelka Design Bureau? In this regard, I consider the installation of sculptures8 in the urban space of Krasnodar to be the worst project of the Typography. Nobody needed them except for artists and the administration; they were created in isolation from the contexts, from the desires and needs of local residents. They were no different from those ugly bronze eye sores that constantly appear at the behest of city administrations. Moreover — this project reproduced the same violence and hierarchy, generating expertise — “we think that these sculptures are worthy, but these are not.” But who should decide this?

Stepan: Damn, well, it depends on where you look from.

Elena: This was about creating a lifestyle. The space of the first Typography looked, so to speak, anarchist, and this attracted people who wanted to appear anarchists or counterculturalists. And many of them criticised me because everything had changed and turned from self-organization into an institution.

Stepan: Well, the ZK/U in Berlin, where we are having this conversation, looks like the first Typography. Some parts are under-repaired, and somewhere the walls are not painted — they can afford to work like that. In the second space, we couldn’t afford this because we had to meet the expectations of a wider audience and not be marginalised to be able to change at least something.

Marianna: But when working on a new space9, we turned to its history, its different layers — we didn’t just design photo zones. Maybe it wasn’t obvious to the visitors, but that’s another question, how to make your ideas visible.

Stepan: When you want people to engage in what you do, you must speak in a language they understand. In Berlin, everything is covered in graffiti and people like it, but in Krasnodar, everyone is tired of flooded streets, poor public transportation system, and lame design. Therefore, everyone loves the Krasnodar Park10 so much — it is such eye candy, detached from life, people come there as to a museum.

I think that in our space, we’ve created a universal form. It was clean, there was no overwhelming pathos, a person could come and feel sort of at peace, then turn to our programs, cinema, exhibitions, and library. We created an environment for engagement, not trying to go into confrontation immediately. And judging by the social networks and visitors, it worked. There was a need not only for a different visual experience but also for a political understanding that you can live differently. I believe that in a couple of years, there could be much more people who would not be silent when Typography was declared a foreign agent.

Marianna: Stepan, how did you understand the idea of resisting centralization and the locality of Krasnodar in 2012? How has this idea evolved?

Stepan: It grew from an understanding of the inequality between the metropolis and the colonies. Moscow gets everything, and the only regional museum in Krasnodar cannot make a decent exhibition because there is no money. It was all very annoying. On the other hand, lately, I often think that russian society is already so localised, closed in on itself. Turning to locality was a fight against injustice and imperial colonialism, and at the same time, it created isolation. Many institutions are trying to preserve themselves in the conditions of war, which further strengthens this localization and leads to even greater isolation from reality. Our emphasis on locality also created a certain isolation. Why did we cooperate so much inside russia? Why didn’t we do more exhibitions with artists from other countries?

Marianna: It is important not to forget that emphasis on locality also derives from economic conditions. Cooperation with artists from other countries demands at least being able to transport the artworks, which both you and your partners often can’t afford.

Stepan: Perhaps I am now talking about this from today’s perspective. In the early 2010s, there was still an opportunity to break out and make locality international. Later, opportunities for cooperation began shrinking: when artists from Germany or France participated in an exhibition, Center E11 to came to check what the exhibition was about.

Elena: It seems that this is a huge problem everywhere in russia, which we discussed a lot with artists Dzina Zhuk and Kolya Spesivtsev, and Kirill Savchenkov. Why were there no connections between institutions in russia and in the post-soviet countries? Kirill then said that institutions cooperate on the same scale; in russia they are either huge oligarchic monsters in Moscow, who tend to patronise and give advice or self-organizations and state museums without money. And the institutions in Yerevan, Tbilisi, Tashkent, Almaty or Kyiv are medium-sized institutions that have grown out of self-organizations or are still self-organizations to one degree or another. And in russia, there were almost no such institutions, except for the Typography.

I have been thinking a lot over the past year and a half about how Typography needs such projects and how important it is that we work more with artists from the post-soviet countries — from Belarus and Ukraine, the countries of Central Asia, and especially the South Caucasus, because the Caucasus is a region and locality, to which Krasnodar relates greatly.

Why did I only begin to think about this recently? This could have helped to understand not only the colonial and imperial history of Krasnodar Krai but its condition in the present time as well — but it seems that this understanding came too late. I remember how in 2017, together with the ZIP group, we organised the “Mozhet” festival in Dagestan and Vladikavkaz, North Ossetia. Why didn’t this understanding come then? We met museum workers; they talked about mythology, local traditions, about the fact that Stalin was an Ossetian. It was a depoliticized interaction, with only a general desire to do something locally. It seems that some general research, awareness of the Chechen war and personal interaction with Lilit, Andrey and Katya, her very personal stories about the Crimean Tatar family, about deportation, the loss of home, the loss of family, pushed me to this realization much more effectively. But it was apparently too late.

Marianna: Why? When making “Identity Department” project, you tried to figure things out by gathering a group of people who supposedly specialise in various processes in Krasnodar and the region. And in my opinion, it really was an important attempt. I remember participating in one of the orientation meetings and realising that I didn’t have any formulated idea about the city where I was born. What kind of work was done with this information, what kind of exhibition came out — is a topic for a separate conversation.

Elena: Yes, everything revolved mainly around the Cossacks as a facade community designed and used by the state, although there is one step from Cossacks to understanding not just imperial but colonial history; but everyone managed to get around this, speaking rather about the relationship between the center and the periphery than the metropolis and colonised peoples and communities.

Marianna: I also understood decentralisation quite pervertedly, trying to build a conversation with other centers; I was happy to make connections with film distributors from Europe and America or when they agreed to screenings in Krasnodar, which they had never heard of. For example, we managed to negotiate with many European directors for the “Training Fantasia” film program, and I was very proud of this. This logic now seems problematic.

Elena: At some point, I came up with a rule for myself that in every exhibition we do, at least one local artist and one from another city should participate. But then we do a huge project — “Training Fantasia” — and I realise that we have three artists living in Moscow and only one from the Krasnodar Krai.

Marianna: I would also like to discuss why each of us refused a public platform in Krasnodar. Some of our colleagues from other cities who stayed to live and work in russia publicly or privately discussed the shutting down of the Typography as a betrayal of our audience in Krasnodar or, I don’t know, a weak gesture.

Stepan: Speaking up against the war in Ukraine is a struggle. We couldn’t hide our position and create decorations, pretending everyone understood what was going on. We simply cannot say that art stands aside. We would cease to exist as artists if we didn’t make this statement.

Elena: I don’t think there was any way we could continue to do something publicly. After all, there were calls from the police “about the dissemination of illegal information” — that is, about our posts. We could probably delete everything and pretend nothing happened, but what would we do? Exhibitions? Well, I don’t see much point in that. But given the increasing attention, we got from law enforcement agencies over the past year, it would be difficult to continue working even like this.

Marianna: I am upset when people claim that we allegedly attracted everyone’s attention, hyped up on our antiwar statements and happily left for another country where everyone praises us. If we wanted to, we could have “taken advantage” of this earlier by making the FSB visits public. But in 2021, we often worked at the Typography for 12 hours, and we would have been ready to do this in 2022, too, if it wasn’t for the war.

Elena: There is very little hype here: you come to another country confused, don’t have the energy to look for an apartment and don’t understand what to do. It’s good that we decided to pay all Typography employees three salaries at once before leaving, and we had money. I think that having left, we created the opportunity to continue working in Krasnodar, too.

Stepan: It occurred to me that our space could probably be considered such a privilege, and we decided to give it up in order to make a political statement. And many want to keep their privileges. I also had the privilege — my house, I felt comfortable in it…

Elena: It seems to me that talking about our space as a privilege is fundamentally wrong.

Stepan: We had some kind of power at the expense of work, we accumulated influence.

Elena: Yes, and it was completely undone in one moment.

Marianna: No, I disagree that it was undone. Yulia, who manages humanitarian aid collection, said that many volunteers came to help because they were Typography visitors, and that’s how they knew her. Typography has created circles around itself, communities we don’t even know about.

Elena: Yes, I meant to say that it’s wrong to talk about space as a privilege because it was not given to us. It was our daily hard labour. The privilege is that we are all white passport holders; we have a place to live. Stepa and I are in Germany; Stepa has a national visa — this is a super privilege. And the fact that we decided to no longer continue with Typography as a space is not our “willful decision”, it was forced by the violence of the authorities, who created conditions in which it was impossible to continue working — the war, the law on “discrediting the army”, introduction of foreign agents registry.

Marianna: Speaking out about your positions is the most important cultural work, especially during the war. It is dangerous not only because you can be incarcerated but because you appear vulnerable against the course of events. Do you remember how, after a few months of russian armed aggression in Ukraine, the slogan “No war” became irrelevant? And the criminal prosecutions for it are being carried out to this day. And then I think about the radicalization of the position. Let’s say today you agree that the russian federation should seize to exist and the national republics should be separated. Already at this stage, you lose many “allies” from the circle of colleagues working in contemporary art. The big question for me is: is there a line that I consider radical? Is there a point where Typography stops revolutionizing and changing? I don’t know how my position will change, so it seems important to fix it regularly to keep track of it. So far, for me, there are no such cultural projects (exhibitions or film screenings) that could be more important than the working and leisure conditions of those who produce them and the capital that stands behind them. Coming back to Lena’s point about indulging the liberal agenda and resistance, I believe that there is no art so great that it can’t not be made, no books whose publication would be more important than warm houses. Culture does not make any sense if it does not correlate with what is happening in the world.

Political Subjectivity

Marianna: It’s super interesting what Typography will look like in 10 years. What political views will we share? What do we consider important? Do you remember when you recognized Typography and yourself inside it as a political subject?

Stepan: From the very beginning, I saw myself as a political subject, as well as art and Typography. Probably, as ZIP Group, we tried to balance between direct political gesture and soft power. That’s what Typography was about — not acting directly but through experiences inside the space. For me, this is a fundamental point: space can be political. We strived for this, approached carefully, and collected brick by brick. But that doesn’t work anymore because russia is using direct aggression. Putin’s propaganda has been undermining the protest movement, and it won. Perhaps we just needed a little more time.

Marianna: Do you think that if Typography had existed for a couple more years, it would have helped Putin go?

Stepan: We would have more like-minded people working, as Marianna says, in circles that we don’t even know about. In recent years in russia, there were new institutions created that think in terms of diversity and changes in society. Now we seem to have scattered. There is no feeling of a common movement.

Marianna: The problem is that politics, like money, is perceived separately from art — not only by those who seem to be our obvious enemies but also by those who seem to be allies. You’re talking about self-organised initiatives. But were they all trying to change the economic and political patterns in the country? Or were they doing something in a decorative way? For example, Chicory Center for Contemporary Art, now — in 2022 — is going to launch a glossy magazine. What is this?

Stepan: Well, Chicory is post-irony. As well as types of platform shit like TZVETNIK12. The ultimate depoliticized liberal joke on everything. Although at first, it seemed that they thought differently.

Elena: My political subjectivity and work in Typography were connected with the desire to redistribute resources. I remember clearly saying to myself that I would no longer be doing anything in Moscow. My work aimed to support artists and create opportunities for them, as we once wrote together with the ZIP Group in the Typography’s mission. This, of course, was politically conscious. But it seems that I did not always see the art we showed as some kind of political force. We had exhibitions of local artists who often did not express any political position at all, for example, the KUS group with their abstract paintings. Now I see it as a problem.

Marianna: Why did you make exhibitions at all, and why did you stop doing them after February 24?

Elena: Initially, I wanted to do educational projects. Then we got a grant from Garage, Oleg Safronov became director, and the ZIP group decided they needed a curator, so they offered me this role. To be honest, already back then, I’d been thinking for about two years about not wanting to do exhibitions because I was tired of them. And if we’re talking about today’s russia, I see neither the point nor the interest in doing something allegorical. But it turns out that I continue to deal with exhibitions one way or another — and now I am participating in preparations for Өmә exhibition.

It seems to me that many exhibitions are made by inertia, but the main advantage of this format is that you can come and see it alone or in a group when it suits you. The exhibition does not imply a momentary collectivity, unlike watching a movie. A couple of days ago, I went alone to the Forensic Architecture exhibition, and it made me burst into tears. I realised that Forensic Architecture usually works at the invitation of social organisations that emerge to counter racialized and police violence. And these organisations have a very strong influence on the formation of the political field. So I began to think about russia, where these social movements are now being destroyed. In general, Typography was also such a social movement that, in one way or another… propagandised alternative values (laughs).

Marianna: Now, all the people who came to us for coffee are realizing that they’ve been pollinated with non-traditional values.

Elena: When Marianna and I were discussing what kind of introduction about Typography we could do for the new site, we came up with a timeline that would align events and posts on the Center’s social networks and political events. How has Typography reacted to them since its inception? We wanted to carry out such work and assess our responsibility. I read posts from 2012 to 2015 and saw that you, for example, reacted when the first law on LGBTIQ+ propaganda was passed or when Navalny was convicted in 2013. But when Crimea was annexed, the war began, and a Boeing was shot down — there were no posts. Why? Do you remember what the reaction to these events was like in Typography, within the ZIP group, yours personally?

Stepan: In 2014, I had the feeling that we lost. There was complete apathy. The protests that began in 2011 have been lost. Political reaction, as it seemed in 2014, became impossible, although back in 2013, we made BOP13. Putin’s victory was obvious, and it drove me into depression. It was difficult to understand what to do in this situation.

Elena: Did you touch upon this in your works, for example, or in the works you showed in Typography?

Stepan: I think that we have just gone into autonomy and focused on locality. As if we lost in the political field and moved into the social field.

In Krasnodar, there was also a wave of repressions against political activists who advocated the secession of the Krasnodar Territory after the annexation of Crimea — EcoWatch, Alexander Mandregelya and others14.

In 2013, there was a case — we were flying to Norway and got a call asking where we were going, why, and where we got the money from: maybe from the Georgians? It was some dude from the FSB, they monitored our movements.

Elena: Wow! In 2013! During our conversation, we mentioned the persecution of Typography several times. We made compromises and did not always make these situations public — visits from FSB, interrogations until two o’clock in the morning, and equipment confiscations. This began to happen to us only in 2021 — and we were silent about it. Firstly, we wanted to continue working and considered it important, and secondly, we did not want to endanger ourselves and those who worked with us. But this did not just happen to us, but to institutions throughout russia — and almost everyone was silent about this. I remember my shock when Anton V. spoke about the fact that everyone has curators from the FSB — I laughed then, and a week later, we had an FSB officer at the exhibition — welcome! I constantly ask myself: would anything change if we didn’t stay silent? If we all spoke openly and publicly about pressure from the authorities?

Marianna: Yes, but at the same time, I remember a tired policewoman who came, probably after working hours, inspecting a claim that we had LGBTIQ+ propaganda among minors. The person who made a claim was some guy from the “Male State”.15 He came to us several times with different girls, and we even had videos of his actions of sexual nature towards them. He allows himself to act like this and then writes statements against us. The policewoman asked: “Well, everything is all right with you, you don’t show anything to anyone here?” We were like, we don’t show anything! She signed off and left.

Elena: Well, this just shows that different departments and law enforcement services are not synchronised.

I also wanted to discuss something I noted when you, Marianna, talked about Eldar, who rejected your offer to make an exhibition. In the first couple of years of Typography, the number of exhibitions of male artists was incomparably greater, there were two or three exhibitions of women artists. You declared the need to fight patriarchy but, at the same time, seemed to reproduce some of its patterns. I believe that Eldar often used his position in the Typography in relationships (now it’s called abuse). I would not be surprised if he was also involved in gatekeeping women.

Marianna: I wonder how many people who participated in Typography shared all the values we discussed today and perceived them as fundamental for the Center?

Stepan: We’ve learned a lot with Typography. The processes were intuitive, even in our own artistic practice. Therefore, there were a lot of screw-ups.

Marianna: That’s why I believe in the manifesto, as a document that speaks out and sets values that can be appealed to.

Stepan: Let’s see how it will be in 10 years. Maybe we will change radically as well.

Marianna: I hope not. But some wording will definitely seem out of time, and that’s okay. It is important not to try to erase your past, to turn a blind eye to mistakes, but to critically evaluate them. When we discussed this timeline, we thought that you can look at August 2022 from 2012, or you can look at 2032 or more distant points — and this would give a different perspective. Remember when we were discussing the ideas for the tenth-anniversary project, we wanted to try to imagine what we would be doing if we weren’t making art and working at Typography? What was this decade of the Center like for you? And how do you imagine it in ten years?

Elena: First, I wanted to think about what institutions were needed now and invite colleagues from Armenia, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, and Ukraine to join this discussion… It seems that the war and forced migration allowed me to do something outside the Typography and art. But, as these ten months have shown, I still do roughly the same thing, but in a different way. In February, I promised myself that now — only direct actions against the regime, but I quickly burned out and realised that this was not for me. And then, I realised that what we are doing can and should also be considered activism: KISI, the residency.

Stepan: I lack the opportunity to be an artist right now. If we imagine an exhibition in a parallel reality — I would like to meet everyone because I was very worried and still worry about the weak solidarity between the participants of the russian cultural field. Marianna, what do you think?

Marianna: I don’t know, maybe we should try to work on a manifesto.

Stepan: Manifesto as a format definitely confronts post-irony, and that’s good.

Elena: Thank you for this conversation!

Marianna: Yes, although it seems to me that it still didn’t manage to grasp what Typography was and is.

- KICA — Krasnodar Institute of Contemporary Art. It was founded by the ZIP group in 2011 in their workshop at the ZIP factory (Russian abbreviation for Measuring Instruments Plant) in Krasnodar. In 2012, KICA moved to the Typography coworking in a former space of “Soviet Kuban” typography (printing house). Later, it transformed into a culture center and then — Center of contemporary art “Typography”. At first, KICA functioned as an experimental exhibition platform and educational initiative. Since 2014, it has become a regular educational course called “The Art of Rapid Response.” Read more about KICA here.[↩]

- Eldar Ganeev, Vasily Subbotin and Evgeny Rimkevich are artists, and at that time all of them were participants of ZIP Group[↩]

- Evgeny Pavlovich is a businessman and philanthropist from Krasnodar. Since 2013, he has been the main patron of Typography[↩]

- Kublog is a local online media, which resumed its work in 2022. Old content is not available on the new website[↩]

- For security reasons, we do not disclose the full names of people who supported and continue to support Typography[↩]

- MOST is an auction of contemporary art organized in Krasnodar by Roman Levitsky and Oleg Goncharov in 2014. MOST auctions in 2020 and 2021 were held at the Typography, the 2020 auction was charitable — all profits were transferred as a donation to the Typography. In 2022 the auction hasn’t been held. Auction website.[↩]

- According to the exchange rate at the end of 2017, 25,000 rubles was about 363 euros, 50,000 rubles was 725 euros, respectively.[↩]

- The project for the installation of urban sculptures was initiated by the Krasnodar City Administration. Typography was the organizer of the competition, gathering an expert jury to discuss the applied projects. Artists from Krasnodar and the region were invited to participate. As a result of the competition, three sculptures were installed in the parks of Krasnodar. More about the project here.[↩]

- 5 Zipovskaya Street — the former canteen space of the ZIP factory (abbreviation for Measuring Instruments Plant in Russian) in Krasnodar, built in the 1970s. The architectural project of the Typography included elements of restoration of the building’s original features, attributed to Soviet modernism, such as the “Kislovodsk” modular system, terrazzo flooring, and aluminum tiling on the ceiling. In the 1990s, the building was rebuilt, and in the 2000s, it housed the Oriflame company office and warehouse. Currently, the building is used as a rent-out event space called “Empty Place”.[↩]

- Krasnodar Park is a city park built on the initiative of the entrepreneur Sergei Galitsky and is fully financed by him. It’s more often called “Galitsky Park”. The park was built at the stadium of FC Krasnodar, also owned by Sergei Galitsky, and in its project, in the first place, the goal was to route the flow of fans from the stadium to the parking lot and transport stops. The park is often compared with Moscow’s Zaryadye and is called one of the best parks not only in russia but also in Europe.[↩]

- Center E is a special unit within the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the russian federation for suppressing extremism. The center was created on September 6, 2008. In Moscow, the center was initially set up in the federal police headquarters, but by around 2012, they expanded to district-level police offices because of the protests. Center E is also extremely active in Crimea and in the republics of North Caucasus. Center E is widely known for prosecuting and harassing opposition groups, anti-regime bloggers, environmentalists and other civic activists.[↩]

- TZVETNIK is an aggregator platform, organized by Natalia Serkova and Vitaly Bezpalov for publishing photos of contemporary art exhibitions and promoting certain ways of creating and distributing art. Criticized by many cultural workers, including members of the Typography, for sympathy for right-wing, nationalist and Eurasian views.[↩]

- BOP — Booth for One-person Picket, a project of ZIP group. It was first created for a picket in support of the Bolotnaya Square prisoners, which took place in Krasnodar on May 6, 2013. The BOP was arrested by the police and kept for a year in the Krasnodar District Department of Internal Affairs of the Karasun District. BOP is a part of the ZIP group’s project “The Civil Resistance District”[↩]

- To read more on this, you can follow this link.[↩]

- Male State is an unofficial russian men’s movement that advocates patriarchy, nationalism and racism. Male State participants often staged campaigns of harassment against feminists and activists.[↩]