Neseine Toholya is an artist-researcher in an interdependent relationship with the world. Practices decolonial queer, produces text and other artistic products. Born from the spirit of the era, she graduated from the Pedagogical College in Salekhard, the Smolny Institute for Noble Maidens and the European University, currently a Fellow at the IASS Potsdam. Composes art of varying severity, is in search of meaning, and stands for goodness and justice. Likes Sailor Moon and other Japanese cartoons.

Cu:mpu Tɯal is a phenomenon emerged out of earth, air and what is present in the world in invisible ways. Inspired by myths and dreams, they create poetic sketches outside of time and space.

Translocal Dialogues opens with a series of interviews by artist and researcher Neseine Toholya, who invites three like-minded colleagues to talk about Home. The first conversation is with Cu:mpu Tɯal, an artist from Yakutia. They discuss how the feeling of Рome emerges, what it consists of, and how it is affected by (forced) emigration.

Neseine Toholya: Nowadays, I call everyone and ask what place people can call Home. Can you introduce yourself and then tell me about what Home is for you?

Cu:mpu Tɯal: Hello, I am an artist and researcher from Yakutia. Perhaps, Home is about feeling? Yes, for me, it’s about feeling at home. When you can feel good and calm as if you have some kind of invisible connection with the place. For me, this is Home.

Neseine Toholya: Is there any place on earth that you could call home? I ask because now we all find ourselves in some state of complex migration. People travel a lot, I do, too. I understand that I can’t call Home every place I’ve been to. Still, when I go somewhere, I try to create a space where I can feel at Home. At the same time, only two places for me bear the sense of Home. To some extent, I still perceive my parents’ house as Home. On the other hand, I don’t call it that when I come to visit. It’s their Home, but it was mine for a long time, too. It had a significant impact on me.

My Second Home is an apartment in St. Petersburg, where I used to live. And everything else is just temporary points where I can feel good and comfortable but still know that my Home is somewhere else.

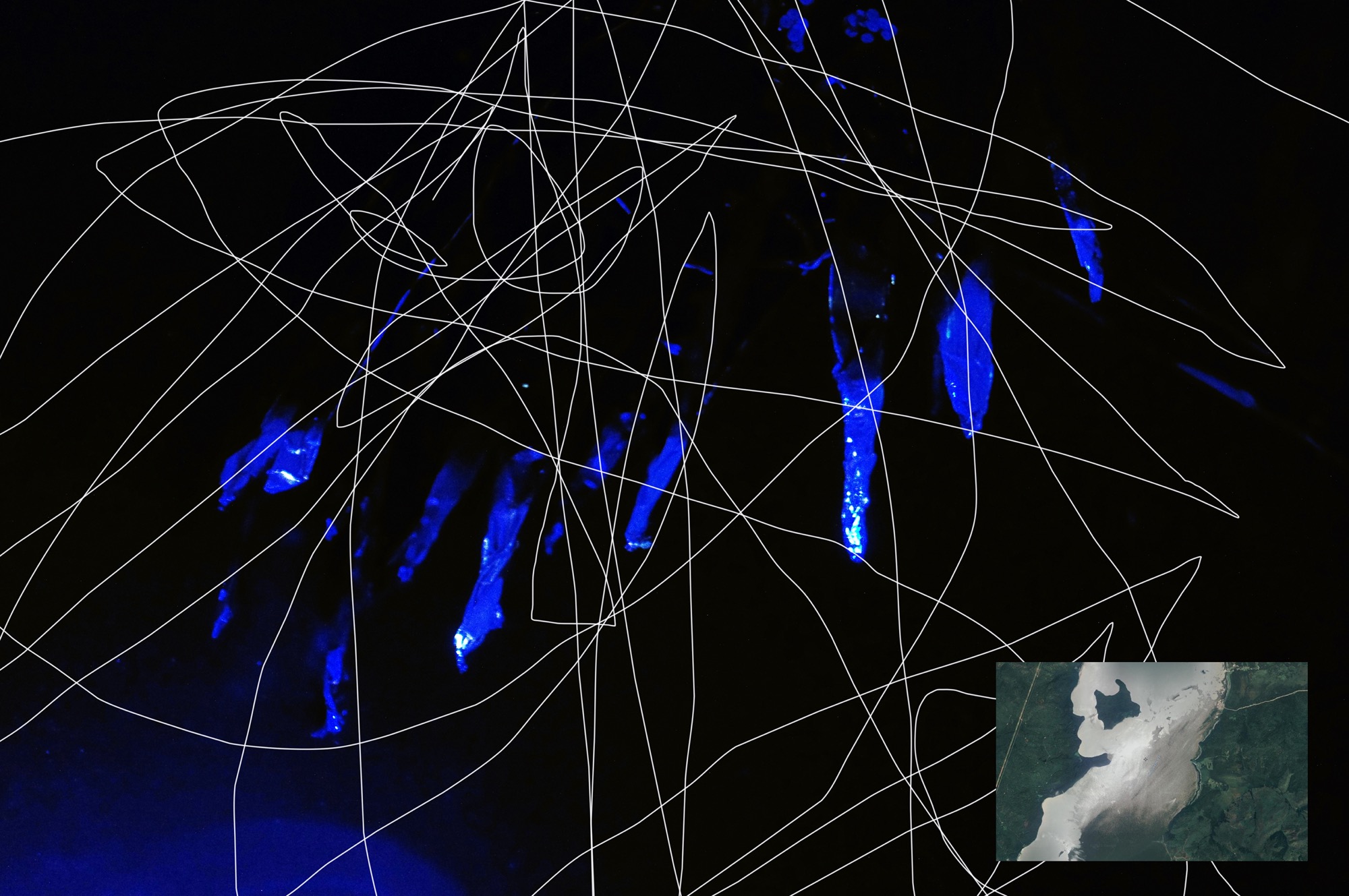

Cu:mpu Tɯal: That’s interesting. So, one of your Homes is in St. Petersburg and another in Yar-Sale, right? My Home is a very sprawled feeling/place. The whole republic where I come from feels like Home to me. Even when I come to a new village or town inside this Home, I feel at home. Because the place is talking to you. It gives you signs, reveals itself so you can feel it. Therefore, a Home for me is not about a specific physical geographical space, such as an apartment or a dacha, but about a place. It has a large trajectory, a sprawling shape. Spreading in all directions.

Now I’m in a place that I can’t call Home yet. When I miss Home, I go to one building that reminds me of it. It is very similar to ураһа — the summer dwelling of the Sakha people. There is a building in the neighbourhood that looks similar to it. I go there to look at it, and I feel better.

Neseine Toholya: I don’t have such a feeling in my native autonomous district. When I come to the tundra to visit relatives, I feel like a guest. I am a guest among the Nenets in the tundra; I’m a guest in the village, a guest in the city. And the Home in my village — I realise that when my parents are no longer there, I’ll have fewer reasons to return. This, perhaps, will be the point of losing my Home completely — the childhood home where I grew up. Although I grew up in several houses as a child, the one my parents still live in remains the symbol of my Home.

Cu:mpu Tɯal: I wonder what this symbol consists of. Is the building itself — a Home, or is it also something that’s inside it? A table, a closet, small objects that you have there. If all these objects are moved to some other place, will it become a Home?

Neseine Toholya: The other day Martha Dashiin and I were talking about the feeling of Home manifesting through objects and things. I said that for me, the object/symbol of my Home, for some reason, is the portrait of my grandfather. It is the only thing I took with me on emigration when I left russia in March, panicking and throwing every dear thing into my suitcase. This portrait used to hang on the wall in my childhood room, and I talked to it a lot in my head. So it became a key and defining object, and I don’t really care about any other thing.

All in all, my old room has already changed so much, and when I come there, I no longer feel a strong connection with it. What is left are moments, not things. In Yamal, the seasons change in their own way, there is a polar day and a polar night, and there is a particular routine in the day that you involuntarily begin to notice. My favourite time is when the sun comes to the kitchen, it creeps through the whole room, and for me, it bears a special meaning connected to the feeling of Home. The other thing is the particular point of view from the window. Another one — to go down under the house: it stands on a piece of land, along with my dad’s sheds. Among them, there is a gap going a little further into a kind of creek-bog with tall grass. I love going to this place; it is also about Home.

Cu:mpu Tɯal: If I think about a material house, I can recall a couple of places. If we narrow the concept of a Home a little, it can also fit into a space like an apartment or my grandmother’s house in another ulus. This summer, I visited the town where my parents were born and raised. My grandmother’s old house is there, and my family’s WhatsApp chat is still titled after its address: this is how much this place is significant to everyone; it always gathered our family. Everything there is made with love. This house was built by my great-grandfather. With its own well, even potatoes grow especially finely there, and there are secret paths nearby to make your way to the neighbours. I think my family lacks this house greatly. When I was walking by, I knocked on the door and said: “Can I come in? This is the house my great-grandfather built,” — they let me in. And when I went inside — it was as if nothing had changed there, although all the objects were different: another cupboard, new chairs… But perhaps because it was made by the hands of a loved one, this house became a place of power for our family. It’s impossible to hide — the new tenants hung a gigantic flag of the republic over the main room, changed the walls and the floors. But everything is arranged in such a way — it’s as if it remained the same. And I felt at home. Like the spirit of my great-grandfather was there. That’s why I entered like I would enter my house, and that’s why the people who live there now are absolutely wonderful. It’s good that they live there now. Such an open and kind family — it’s like we share a Home with them.

Another Home is in Yakutsk; you’ve been there. I got used to it very quickly. Although before that, I had been telling my parents since childhood that I would never leave their house, and they always said: “No, you will grow up and have your own place.” I replied that I had no such plans. When I got a new apartment, I was prepared to get used to it over a long time. At first, I constantly went back to my parents’ to talk, eat, sleep, and just hang out — and then suddenly, I got very used to the new Home. I never guessed that I would develop such a reverence towards it. And there were things like the ones that you talked about when you mentioned the sunlight that pours throughout the kitchen and spreads so quietly as you are watching it, how it is important to you. I had such moments. The moon shines there so powerfully, and you can play with shadows. In the evenings, I often sat in the apartment and played with them for hours. There are always moments that we miss. But there’s also a moon here, and I might be able to catch its glow again.

For me, Home is also about nature, and therefore I do not have a strong attachment to any physical place. If, hypothetically, someone will put me into a plastic box — this would make me sad, and I won’t be able to feel at home. But if I am somewhere on planet Earth and I have access to nature, then, sooner or later, the feeling of Home will come.

Neseine Toholya: For me, a particular type of nature symbolises my native places. The tundra, with all its voids and small forests, is the dearest to me; I feel a connection to it. And if you take nature around St. Petersburg, this would not feel as homely. It is interesting that we can relate the notion of Home to such outdoor spaces. Have you ever had the desire to leave Yakutsk or russia?

Cu:mpu Tɯal: Not really. Well, when you live in Yakutsk, you don’t feel like a part of russia. After all, it’s a republic; people constantly emphasise its geographical isolation, affecting the perception of a republic as something separate. Therefore, there is no seeing ourselves as part of russia — except when it concerns some legal aspects. For some reason, I feel strongly attached to the place. I like to leave Yakutsk only if I know I’m coming back. When travelling around the world, I need to know that I can return to Yakutsk: if there is no such option, then I would prefer to stay. I begin to miss it even after a week away.

Now, so many of us are dispersed in different cities and countries. As we keep in touch, I feel like the Home is also dispersed through many places worldwide. In Yakutsk, people really make a difference. And everyone who’s left wants to go back home — but not to the Home where everything is set against you, anti-you. It is challenging for everyone. I hope that the time will come when it will be possible to come back and, perhaps, we will feel this Home differently. I’ve always left knowing that I would return.

I have friends who have never left Yakutsk, never even thought about it. They are offered to, but they immediately refuse. This idea is not particularly close to them, they just want to be in Yakutsk. I have a lot of such friends — as if there is a strong invisible umbilical connection with our Home. Before leaving, I listened to an audio walk dedicated to the city — I was comforting to know that I could turn on Yakutsk anywhere and just walk with it in my ears.

Neseine Toholya: I also had no desire to leave russia for good. But for me, it’s still russia. I’m not tied only to St. Petersburg, and I’m not tied only to Yamal. My life has formed between them. In recent years, I began to travel to Yamal more often and consider it a place where I can do something and occasionally live. I even thought about spending a winter or a summer there, an entire season. Stay there for a long time to feel the way life goes there. Make something there. It’s a pity that opportunities to do so seem to fade away.

On the other hand, the ideal situation for me is when I can freely move around the world and live in more than just one city. I have places dear to me in many counties, and I have no idea how my future relationship with Berlin will develop. Will I ever miss this city? Will I not want to leave here? Will it become my Home? So far, nothing is clear.

Cu:mpu Tɯal: Perhaps within a month you will already say: Home! No one knows the future and how the relationship with the place may develop. Out of places outside of russia, I felt very much at Home in Sápmi.1 Because the nature there is very similar: trees are not too tall, and the climate is cold. Nature is a big part of feeling at home. And if I go to nature here, where I am, every day and stay there more often, this feeling may someday grow again.

Neseine Toholya: I don’t know of many places with nature similar to the nature of Yamal: Canada, Alaska, maybe Greenland. In Europe, the closest is probably Norway — but I’m not very sure. These are not the countries I feel connected with; I have never been there and can’t judge how they are.

There is a tundra without trees in Yamal — it is not so easy to find such nature. The landscapes of Finland, and even Sápmi, are more southern than where I grew up, and they don’t feel kindred. It’s beautiful there, but it’s closer to St. Petersburg or Southern Siberia. And I can only feel kindred nature in the tundra, on Yamal. The places there are very familiar, especially near the village, where every path is well-travelled, where I already know what awaits around the corner — everything is Homely.

Cu:mpu Tɯal: Sometimes there are sensations, not connected with nature as it is… I remember that when I lived in another country, I volunteered for one initiative where we cooked food and gave it away. There was a huge freezer — everyone would only go in for five seconds and leave immediately, but I went in there and fell asleep. Felt like Home. And often, when I came to volunteer, I asked to go sort the products in the freezer. I tried to stay closer to it because the temperature was comfortable there, and I wanted the cold. When you are in the south, this is very difficult to find.

What’s interesting is what you said about being free to move around and not being too attached to the Home.

Neseine Toholya: At the same time, I am very attached to Home. I just don’t want to be in only one place. I want to be able to go wherever I want. The current restrictions on freedom of movement feel very wrong.

Cu:mpu Tɯal: It seems to me that soon people will become nomads again. There will be fewer and fewer places to live; people will constantly migrate and be in chaotic movements. I don’t know what will happen to the place then — if we are talking about a specific place, for example, Yakutia.

This fall, I even came across a book called “Төрөөбүт буор тардыыта” (Call of the Native Land) — it’s about the feeling of being drawn to one’s native land. People often say, “I can’t go anywhere because I can only breathe here. Here the air is sweeter, here I feel better”. I don’t know how they manage relations with other places now, being forced to move.

Neseine Toholya: When I imagine never being able to come back, it makes me very sad. I can not imagine that I would not return to St. Petersburg, would not return to Yamal, not see those places again. I met one activist here who hasn’t been to russia for forty-two years, and I was like: “Forty-two years!? Oh god…”

I might still be in shock because I was never going to leave. Everything that is going on in my life this year is a complete surprise. It’s something I’d never planned, knew nothing about it. When I left [russia], I faced all this and just went nuts, I was very confused and did not understand what to do, how it all works, or what a residence permit is. All these Anmeldungs and other things. Disorienting. When I went back to St. Petersburg for a visa this summer, I realised how much I love this place. And it was impossible to uproot me from there, I could barely convince myself to leave: I was already running out of money and needed to go to another country to get it. The plane took off — I cried, it landed in another country — I cried, then flew away from that country — cried, arrived in Berlin — cried, just a never-ending horror of tears.

When I left in March, I was not so overwhelmed. It hit hard in August and let go of me only a couple of weeks ago. Or a bit earlier — because I also went to the US during this time. It is even further away, so coming back somewhere closer to Home already feels better.

Cu:mpu Tɯal: And how did it let go of you? How did this release come about?

Neseine Toholya: I returned to Berlin after the US and felt I might as well stay here, much closer to St. Petersburg than in the US. When I was there, I thought to myself: could I move here if I won’t be able to return to russia? And I couldn’t. Something so alien and distant for me there made Berlin feel much closer and homely. Perhaps that’s what brought on the release.

Cu:mpu Tɯal: The realisation that there could be an even more alien context?

Neseine Toholya: Yes, probably. I met different people who emigrated to the US. For various reasons — some went to study, some left russia in February and March. Their experiences are very different, but all of it is very depressing.

Read also:

I’m sorry you can’t find your cream

The second conversation with Neseine Toholya: artist and activist ~several talks about the class aspect of migration and the experience of losing privileges.

The smelly pen is the expression of space-time

The third — and the last — conversation with Neseine Toholya: they recall the objects containing the space-time continuum of their Homes with decolonial researcher Martha Dashiin

Cu:mpu Tɯal: Depressing how they moved or how they live in America now?

Neseine Toholya: The way they feel now. These people are not indifferent; of course, they are very worried about everything happening now. They didn’t just leave and forget about russia — they watch the news and are invested in what is happening. They really want the war to end, they dream that russia will stop being such a colonial imperialist state. To have such a connection with one’s homeland and be so far away — this experience can really fracture you.

Cu:mpu Tɯal: I have friends who moved to Canada and US ten years ago or earlier. They usually know the news from Yakutsk faster than I do. Being far away, they still live as if they haven’t left. That is why they say that it is tough, that is why there are diasporas, attempts to find those who are also homesick to be together to support each other.

Home is also about language. Here I am away from Home: I can call someone and speak my native language, write or read something. And then it becomes somehow easier? When I manage to not forget to support myself this way.

Neseine Toholya: I do not know the Nenets language, so for me, it is probably not so much a part of the Home. On the other hand, I had plans to someday move to Yamal just to learn the language. And I understand that being in Berlin, I am moving away from this goal a bit. But I tell myself that it’s just a period, and now I have to do something else. If I want to, I can always return to Yamal and go to the tundra. This is not yet a plan but an opportunity that I keep in mind. That might be why I am okay with being so far away — as long as there’s this opportunity. If I didn’t have it — if the Federal Safety Service officers were waiting for me at the russian border to immediately put me in jail — then, probably, everything would have felt differently for me. And if I’m not yet in this danger, I know it’s somewhat safer to live in St. Petersburg than in a small town in Yamal. Because there, it’s easier to find and crush me. And in St. Petersburg, you are like a needle in a haystack.

Cu:mpu Tɯal: But in Yamal, you have tundra where you can always just run away and hide…

- Sápmi — in Northen Sami a land traditionally inhabited by the Sámi people.↥